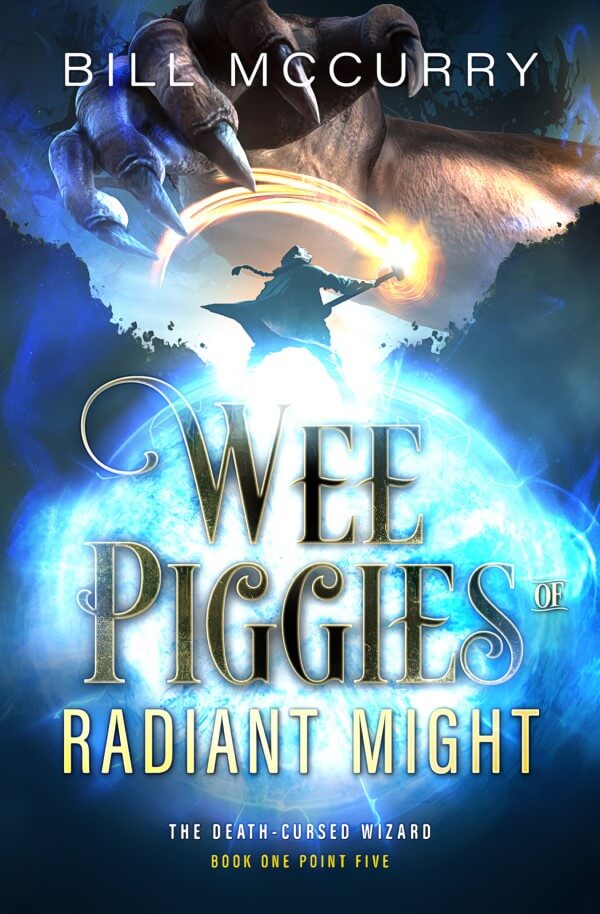

Wee Piggies

of Radiant Might

Companion Novella to the Death’s Collector Novels

Someone is driving the gods insane…

and they weren’t all that stable to start with.

Fingit, the Smith of the Gods, has been mocked by his bickering siblings since the beginning of time. Now he’s their best hope.An ancient enemy cripples the gods’ minds and begins demolishing their realm.

Solitary, bookish Fingit is less crazy than the others. Alone, he creates a shrewd war plan. But is it truly clever, or does his addled brain just think that?

Even if the war plan is good, Fingit needs warriors. But the panicked gods have scattered like bunnies to different realities. Can he collect them before their home is smashed and possibly eaten?

The gods are willful and demented. How can Fingit convince them all to hurl their lightning bolts at the enemy . . . . . . when they’d rather hurl them at each other?

“You may reach up into the tree and pick apples every year. But if you cut down the tree so that you don’t have to reach up, don’t cry next year about not having any damned apples.”

– Krak, Father of the Gods

Sample from Chapter 1

These days, Fingit announced himself when visiting the Father of the Gods, hoping to prevent awkward situations, such as the day he found the old fellow squatting naked in a ditch, giggling and weaving grass into his beard. One could expect eccentricity, especially since existence was so bad just now, but that kind of behavior was disturbing to see in the most powerful of all divine beings.

“Father!” Fingit walked down the tree-blemished hill. Although spring was well along, the trees looked poor. Not diseased, just washed out and puny. He squinted through his spectacles and wondered if he needed stronger ones already. “Father!” Fingit puffed on down the hill with purpose, his modest gut waddling.

The hill led down to a precipice overlooking an immense drab valley bisected by a meandering, muddy river. An ancient stone bench perched at the cliff’s edge. It was ancient in a profound way, since it dated back to the beginning of time as the gods understood it. Krak, Father of the Gods, sat leaning forward on the bench he had built, facing the valley.

Fingit frowned at the back of his father’s head. He’s ignoring me. Damn him. Typical. He wants me to scrape and kiss his feet, in spite of everything.

When Fingit reached Krak, he stood behind his father’s right shoulder and waited to be acknowledged. Krak did not choose to acknowledge him at that time. During the wait, Fingit examined his father. The old man’s hair looked thinner than yesterday, and not just white—almost translucent. His stubbly face did not appear noble and craggy anymore. It looked like crumbled stone in a worn-out net. Brown spots speckled his white sleeve.

Crap . . . his robe is stained. Is he that far gone?

Five minutes passed, and with supernatural force of will, Fingit managed not to squirm. He’s doing this on purpose! The vindictive old turd!

At last, Krak drew a deep breath and said, “My son. What do you want? I’m busy.”

“Um . . . busy with what, Father?”

“Contemplating the existence of my foot up your ass.”

“Huh. You should be nice to me, Father. Nobody else pays attention to you anymore. The worse things get, the more they forget about you.”

“The little thugs.” Krak leaned back and patted the bench beside him, and his youngest son stepped around to seat himself with a sigh of non-divine relief.

Krak glanced sideways at his son. “So, what are you here to tell the old fellow today?”

“Things are great. Better than ever. Trutch just sits under that dead tree and whines all day. Effla has been banging demigods three at a time, and Weldt doesn’t even care. He just drinks wine and makes up songs about lightning bolts and whales.” He paused, but his father just leaned forward and grunted. “Lutigan stabbed Chira’s flying moose through the heart—fourteen times—and then ran naked through the Emerald Grove, pissing on every fourteenth tree.”

“Anything else?”

Fingit cleared his throat. “Well . . . Sakaj committed suicide.”

Krak groaned. “How?”

“She stabbed herself through the eye with a thorn from the Tree of Mercy.” Fingit said it as fast as he could.

His father lifted his head. “That’s not so bad.”

Fingit glanced down at the side of the bench and brushed off some nonexistent dirt. Father’s perspective on “bad” has become skewed. Or maybe screwed up to holy hell.

“She did it just the one time?”

Fingit nodded. Sakaj had once committed suicide every day for a year, and she’d never employed the same method twice. She began with hanging, drowning, decapitation, and all the popular ones. Then she got creative. She crushed herself between rolling boulders. She called Lutigan childish names for fourteen hours straight until he chopped her into fourteen pieces. She threw herself under the Holy Bulls; she tore out her own hair and hanged herself with it; she chewed her hands off and bled to death. Of course, she was reborn each morning. She was a god, after all. But she certainly looked worse and worse every day, and her behavior disturbed everyone else in the Home of the Gods.

After her Year of Self-Annihilation, Sakaj stopped committing suicide and had never spoken to anyone since. She wandered through the withering forests. That was annoying behavior too, but at least one didn’t find parts of Sakaj scattered around when going to pick golden apples.

Well, they were tin apples now. As existence had grown sadder and less robust, so had the apples. When the crisis had broken, the golden apples became silver in a blink, sweet but no longer a near-sexual experience. Soon, the sliver tarnished, producing firm but unexciting fruit. The bronze apples came next and weren’t so bad, mealy but wholesome. Later, the bitter iron apples forced the gods to chew a lot to get them down, and the current tin apples left a film on the teeth and just tasted nasty. An industry of manic wagering had arisen speculating on the next apple degradation. The current favorite was stone, although a militant minority claimed that copper had been unfairly skipped, which would soon be rectified by the laws of existence.

But that wasn’t the point. The point was that Sakaj had resumed murdering herself.

“So, Father, any advice from the divine fount of knowledge?” Fingit failed to keep the sarcasm out of his voice.

“Screw ’em!” Krak sounded almost like his old, mighty self. “Let’s you and me head down into that valley with a couple of cute broads and a barrel of wine, and leave these fools up here to obliterate themselves.”

Fingit stared at his father. “Do you mean that?”

Krak giggled, looked back into the valley, and ignored Fingit.

Fingit leaned back, closed his eyes, and reflected on how impotent the once-omnipotent Krak had become and what that meant for everybody. I never appreciated what we had. Men were always begging to give us power and gifts and their virgin daughters. Then, BAP! Whatever the hell it was fell between us and man, and damn it to the Void for eternity. No more men, no more power. No more virgins, either.

“Father, what do you want me to do? I think the crisis is here. We must do something, or soon we’ll be too weak and stupid to do anything. Don’t you want virgins anymore?”

“Just a little more time,” Krak mumbled.

“It’s been eight years! Just tell me what to do!”

“I could use a drink and a chubby nymph . . .”

Fingit rose with a grunt. “Nice chat, Father. If you think of anything that can save us from an eternity of madness, misery, and terror, you might mention it. You know, just in case it comes to you while you’re picking your toes. I’ll be in my workshop making a poorly designed machine for doing something pointless, and which won’t work anyway. If I’m lucky.” He hurled an impossibly searing glare over his shoulder and then waddled back uphill.

Fingit began wheezing. Glancing up, he spotted Sakaj clinging high in a wasted pine tree.

Is that her executioner today? Is she going to brush her esophagus with a pine tree? Hah! Who cares?

Sakaj normally remained inscrutable and creepy. Therefore, when she began shrieking and throwing pine cones at Fingit, he stopped and squinted at her. Her actions perplexed him. Otherwise, she looked the same as she did every other day—filthy and crazy as hell.

Fingit glanced back toward Krak to see whether the old man was paying attention to his daughter’s more-bizarre-than-usual behavior. Fingit was therefore the first to see a monstrous, green-scaled hand appear from over the precipice and slam into the ground not far from the bench, launching clods of earth high into the air. The hand was enormous enough to seize two chariots at once, and it bore claws as long as Fingit was tall. Monstrous was indeed the proper way to describe this hand, since it belonged to a literal monster.

“Cheg-Cheg,” Fingit whispered.

In the next moment, the gargantuan, purple-feathered head of Cheg-Cheg, Dark Annihilator of the Void and Vicinity, rose from below the precipice. Its great, furnace-bright eyes squinted at Krak. Its maw—which could eat four chariots at once—opened and released a roar that promised unremitting destruction. The immense volume smashed Fingit onto his back.

Fingit sat up, blood streaming from his ears and nose, and he saw the beast clambering up onto the precipice. Based on eons of fighting this creature, he knew it would continue clambering until its entire three-hundred-foot-tall self eclipsed the bench, Krak, Sakaj, Fingit, and all the pine trees within sight.

Cheg-Cheg had, from time to time, made war on the gods, at intervals mysterious to even the cleverest among them, or at least to Fingit, who considered himself the cleverest. No one knew why the monster appeared from the Void to assault the gods and all their works, but in each conflict, the gods had prevailed only by employing all of their might and guile.

The Annihilator was now stalking the gods’ realm again, but the gods had grown punier than a modest breeze. Krak hadn’t summoned the impossibly searing light of the sun in years. Fingit’s Hammer That Crushes Souls was propped in the corner of his workshop with dirty laundry hanging on it. All that the gods had remaining was guile.

Fingit employed all of his guile by standing, running away three steps, running back toward the monster five steps, and halting with a slack mouth and twitching eyes. Krak stumbled uphill just as Cheg-Cheg snatched the timeless granite bench and shoved it into his maw. The landmark disappeared with a rumbling clatter of teeth against stone.

Krak slipped to his knees, and Fingit sprinted to help his father. Just one stride away from the old man, Fingit encountered one of Cheg-Cheg’s immense, leathery black feet capable of crushing twenty demigods with one stomp. One of the foot’s pearl-white claws smacked Fingit an incomprehensible blow. Fingit’s skin hurtled fifty paces away, carrying inside it dozens of smashed bones and a fair number of ruptured organs. He landed on his side, almost blind with pain and unable to move, speak, or breathe.

Before Fingit’s eyesight faded, he saw Cheg-Cheg bend down and slice Krak in half as if plucking a daffodil. His blood splattered over a great expanse of sad grass that perhaps hoped to be better nourished on this divine blood. The monster seized both halves of sundered Krak, hurled one across the valley, and chucked the other uphill over the horizon. Fingit wept as he watched his father’s majestic head flop around on his airborne torso.

Fingit was losing the ability to feel pain when Cheg-Cheg grabbed his destroyed body. The monster hauled Fingit up high above the bloody, grassy ground. As he dangled Fingit above his fetid maw and prepared to consume him, Fingit closed his eyes.

I hope Dad doesn’t act like a jackass about my letting him get cut in two.