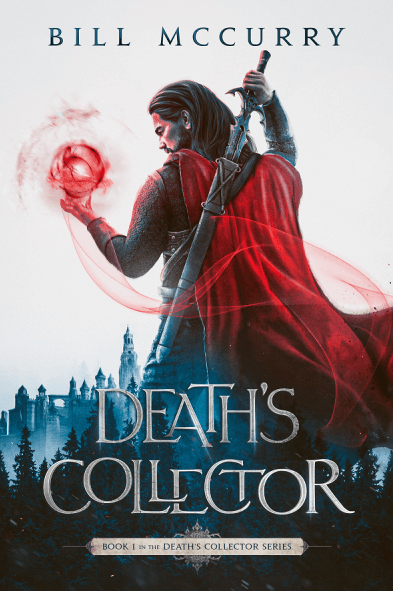

Death’s Collector

Book 1 of the Death’s Collector Novels

A wizard compelled to kill. A slaughter he vowed to prevent. A murderer who pissed off the wrong guy…

Bib the sorcerer hates how much he loves his job. Cursed by the God of Death to collect lives, he focuses his thirst on snuffing out only lowlife losers and contemptible ass-clowns. But when innocents under his protection are brutally murdered, Bib flips the switch on the ultimate revenge spree.

Bent on obliterating the bum responsible, Bib is more than a little miffed when he discovers the shocking truth about his own degenerate nature. But knowing the type of killer he is inside, the reluctant hero won’t be stopped until he mows down every evil dude in his path.

Can Bib fight his way to redemption before he loses his soul to bloodlust?

Death’s Collector is the first book in the darkly humorous The Death-Cursed Wizard fantasy series. If you like snarky heroes, top-notch magic systems, and epic sword and sorcery, then you’ll love Bill McCurry’s addictive tale.

“When you bargain with gods there are no good deals – only bad deals and deals that are less bad.”

– Bib the sorcerer

Sample from Chapter 1

I often forgot the real reason why I murdered people. Some days I told myself I was cursed to do it, and other days I admitted I took this curse onto myself, that nobody moved my jaw up and down to make me say yes. Rarely did I recall the real reason. I murdered people for love.

On the day I perched downhill from Crossoak village, I had just about forgotten that love was a reason for doing things. The village kids ran around behind me, smashing wildflowers and screaming like Death and his five pallid whores. I appreciated flowers, but I didn’t say anything to the whooping mob. They exhibited a shattering fear of me on occasion—so gigantic it probably seemed like a game—and they tended to forget about it unless they concentrated on being terrified. It was a good sight healthier than their parents’ grinding dread, hiding in their houses when I walked past and making folk magic wards against evil behind my back. Anyway, some of the less obliterated yellow pin-blossoms were already pushing up from the grass. It was a shame to get blood all over them, but there it was.

I hummed a little nonsense song under my breath as I watched the three ass-dragging ex-soldiers two dozen paces downslope from me. They glared, their swords pointed at my face and their teeth bared. They also fidgeted and whispered sidewise to each other, which undercut their show of ferocity, but they hadn’t sagged and trudged off down the slope yet. One was chubby, one looked strong, and the third was just a boy, really. In my head, I named them Rotund, Nasty, and Pup.

I scooched my butt to a less splintery spot on my barrel and let my feet swing like raggedy pendulums. I had rolled this barrel here past the edge of town a month ago and tipped it on end for a perch. I’d grown tired of standing around while thieves and murderers dawdled over how to kill me. These three were dallying for an uncommon length of time.

Onni shuffled up from the lane behind me. He was striving to be unobtrusive, but for him, stealth amounted to holding his breath between wheezes, so he sounded like a horse about to collapse dead. I glanced and saw him wipe his sweaty palms down the front of his nice blue jacket, which gaped at the belly. He whispered, “Bib, they’re the first ones in a week. Maybe they’ll just leave. Do you think they might just leave? I think they might.”

I kept humming and shrugged. The rough-patched men hadn’t shifted as much as a foot. Rotund had lost his helmet somewhere on the trail, and his blond hair stood horrified in all directions. His friends had kept hold of their stained and torn gear, but their shirts hung loose.

Onni shuffled down to face me from the side. He was a good-looking man; even when pinched and anxious, his face was almost beautiful. “Could you please make yourself a hint more . . .” He sighed. “Intimidating? It might frighten them away.”

“You mean your heart doesn’t fairly shrivel from standing beside my imposing self? I do admit that my hair’s less red than it was, and I appear lean and a little shabby, but they should still be awed by my moral courage.” I smoothed my beard, which was grayer than my hair.

“Um, as a sorcerer, perhaps you could do something sorcerous? Turn them into . . . something?”

Without looking at him, I said, “For these sad fellows? Such a profligate indulgence in magic might change every person around in ways we can’t even imagine—if it didn’t destroy you outright by lightning, or a plague of vermin.” It was a good excuse to use when people wanted to see something shiny happen, and I didn’t want to admit I’d been tapped out of magic for years.

Onni coughed and scooted back a few feet. I winked at him, and he looked away. He settled for looking at something unlikely to engage in violence, a tree he must have known well, since I imagine he’d seen every day since he could walk.

“You can’t know what will happen, Alder Onni. They could come back tonight and slice off your head, and I can’t allow such an occurrence. I don’t want it said that I cheated you.”

To be frank, I didn’t want them to go away. They’d sure as blue skies earned death for doing some horrible shit somewhere. The anticipation of killing them was pleasurable, as good as knowing that a book and a hot bath were waiting, back when I could indulge in such opulence.

At last, Rotund yelled, “Go off and piss on your pillow, old man!”

I almost objected to that characterization, even though I was indeed old enough to be the little muck-sucker’s father. Instead, I called out, “You have no reason to be harsh, sir. We’re not overly violent people. Pass us by.”

Rotund grinned and Nasty leaned forward. Rotund said, “We’re taking your food, and wine, and whatever the hell else looks good in this rat turd of a place.” Pup nodded and shook his sword.

I created a masterpiece of a smile. “There’s a town just beyond us, popping with delights! You can luxuriate in the laps of nubile women before the sun sets tomorrow.” In fact, the next town up the road mustered a standing guard that would mash these fellows into grit and rancid butter.

“Gut yourself, you pile of pig vomit! We’re not walking around to some other damned town!”

“You do yourself a disservice. Life is chancy, and we have nothing worthy of a man like you. Pass, and I myself will bring you a mug of good beer as you walk around us.” I made my words confident and deferential at the same time.

Nasty said, “The bastard’s poking fun! Let’s kill him!”

I slipped down and stood beside the barrel. I looked hard at them and imagined ways I might murder each one. I could disarm the tubby one and break his neck, but there was no need to humiliate the man. I might stab him through the armpit and cut the big artery in there. He’d die in seconds. I smiled at Rotund and gave him a little nod.

Rotund may have known one or two serious killers. When I smiled, he stiffened and grabbed Nasty’s arm. “We’ll go around! We don’t mean anything.” He yanked at his confused friend. “Really, we’re sorry.”

Behind me, Onni exhaled like a fresh breeze. I remembered the song I’d been humming was something I used to sing to my little girl.

I bounded toward the idiots, drawing my sword as I ran. For a second, they just watched me. I have often seen such behavior, and I suspect part of their minds didn’t quite believe I was coming, which paralyzed them. I whipped a neat slice across Rotund’s bicep. He squeaked as his sword hand dropped useless, while Nasty hurled a professional cut at my head. I arranged to be somewhere else when it arrived by stepping inside his swing, almost belly to belly with him. I sliced hard. When I stepped away, he held his guts with both hands.

Pup lifted his sword for a blow that would chop me in two, so I popped him in the mouth with my pommel. As he staggered back, he dropped his sword. He fell and grabbed at the air with both hands, just in case some invisible rope or fence rail happened to be there.

Rotund sprinted away, holding his arm, swifter than I would have credited. I ran him down in a few seconds and tripped him. Before he could roll faceup, I slipped my sword into the base of his skull.

The disemboweled Nasty had slumped to his knees, begging his mother to make it stop hurting. I made a relaxed thrust through his left eye. He collapsed and went quiet with a shudder.

Pup had grabbed his sword and stumbled upright, his mouth full of blood and probably a broken tooth or two. I pointed my sword at his heart, and then I made my damned self stop.

I couldn’t have explained the act of will required not to kill the boy, not in a proper way. The closest comparison was ridiculous. I might describe the willpower needed to hold off pissing after drinking beer all night, with every part of the body and every single thought squeezing and grinding to just let go. I felt shame describing my compulsion to kill human beings in terms of draining my willy into a pail, but there it was. I wished that Harik, God of Death, Trafficker in Curses, He with the Saggiest Tits in the Heavens, would receive acid-laced scorpions into all his tender orifices for eternity.

I waved my sword at the boy. “Go. Go home. Get a girl and stop playing with swords like an asshole.” Slack-jawed, he blinked a few times, shuffled back, and stopped, wavering in place. I shooed him with my free hand.

Pup might as well have explained his intentions to me in detail. Hell, he might as well have sung them loud enough to echo off the hills at me. He spat blood on the grass, and then he wiped at his bloody chin. He lifted his sword, and his hand didn’t tremble all that much, which impressed me.

I turned away and began walking. “I hear my woman calling! I think I’ll go home and pound her in our bed that I made from the bones of young fools.” Of course, there wasn’t any woman calling, or a bed, but I hoped it would make the boy think.

I heard him suck air, and I heard him running up behind me. I turned and opened his throat, easy as brushing a fly off my shoulder. Blood sprayed, a lot of it, and he collapsed onto his side. He stared at me with his head cocked, working his lips like he wanted to make words. He died there, trying to tell me something that I guess he thought was important enough to be the last words he’d say.

Turning away, I made myself not look at him, but Harik’s nuts. It was satisfying.

Onni looked pale and clammy, as if he might vomit. He had vomited the first few times I’d sent visiting deserters on their way, by which I meant killing them like they were dim chipmunks. I strode past him toward the small town square and said, “Another job done, and done with aplomb.” He fidgeted with the wooden buttons on his nice jacket and didn’t say anything.

I tossed a copper bit to the closest boy. “Keep watch, young sir. If ruffians approach, you know where to find me.” I put some extra swagger in my walk and headed for the town’s modest tavern.

The people of Crossoak were a mass of faceless spuds wearing scratchy, mud-colored clothes. They didn’t think much of me, either. A few stared at me wordless as I passed, mashing themselves far back so as not to stand on the lane while I walked there. Most wouldn’t look at me. Some rabbity ones cowered inside and wouldn’t peek out. I had been there more than two months, and I’d never struck them, cheated them, or even yelled. I hadn’t called any of them nasty names, even though some of the oafs deserved epithets that would strike a meek person dead.

Over generations, the people of Crossoak had struggled their way up to the summit of inoffensive ignorance. They were proudly superior to all outsiders and all the things they had never experienced for themselves. I couldn’t chide them much for that. They lived better than almost any near-destitute folks I’d ever seen, so they were due a little conceit.

Crossoak’s founders had raised their town around a titanic oak tree in a mountain valley. They enjoyed good water, and the dirt would sprout crops if you smiled at it real big. Soft grass grew everywhere, and you couldn’t beat the damn stuff down if you tried. Timber and stone were close, neighbors were far away, and visitors were few. If they had added some gambling houses and whores, I might have considered retiring there.

The townspeople built their homes and barns solid, out of cut stone and unfinished oak—good for hiding from strangers. When hungry deserters had started showing up three months ago, hiding had proven a feeble strategy, so Onni had sent for help from the next town up the road. That town’s people were disinclined to go off and get killed in the defense of Crossoak. But I was there, and getting bored, and the venture seemed like a fine opportunity to kill a lot of people. Maybe help some people. If the chance presented.

Crossoak’s residents had cheered like screech owls the first time they saw me kill some deserters. They didn’t cheer anymore. The crowds dwindled after the first two weeks, and by the end of the month, nobody except Onni witnessed how well I was protecting them. He admitted that everybody had taken to hiding in their houses as much as possible, since they never knew when bloody violence would arise.

A few days later, I mentioned to Onni that I missed seeing the kids play while I sat outside. That afternoon, children resumed chasing and playing grab-ass all over the village. I questioned Onni about it that night, and he admitted that the villagers had decided to let their children watch all the killings rather than risk making me mad.

“They’re afraid you’ll kill them, Bib,” Onni had said. “Cut off their heads.”

“Krak and Harik! Why would I do that?”

“They don’t know. They don’t understand you, not any better than they understand a tiger. They just know if you decide to kill them, they’re helpless.”

I began to understand and respect the villagers’ fear, and even feel some of it. If I didn’t leave town soon, they would gather into a mob and batter me to death in my cot, or lock me in a house and burn it. Fighting prowess meant nothing against fifty men armed with assorted farming implements. I should have left right that instant.

But what if I left and some of Rotund’s buddies showed up tomorrow? Dead kids couldn’t smash wildflowers, and renegade soldiers had already killed one little boy before I showed up. I decided to wait a few more days. Maybe I’d make a little camp outside town and hide like a bunny at night.

I strolled into the dim, meager tavern like my family had owned it for twelve generations. The plank floor and tables had soaked up thousands of meals’ worth of cooking smoke. “Hello, Sunflower!” I said without interrupting my journey to the table where beer would soon arrive. Nobody else patronized the tavern just then. Proper people worked in the middle of the day, and everybody stayed out of the tavern while the unaccountable murderer was in residence.

The old, stringy woman who owned the tavern was as harsh a slice of bitterness as I’ve ever met, so I had named her Sunflower. Only when I sat and reclined against the wall did she move, forcing beer from a keg into a wooden mug. She crossed to my table in a dozen dancers’ steps and slammed the mug down like she was killing spiders with it.

When I lifted the mug, my hands decided that the period of post-murder satisfaction had ended. They jerked and tremored hard enough to slop half the beer out before I set it down. I flapped my hands to dry them, and then added Rotund, Nasty, and Pup to the tally of men and women I’ve killed. I had hoped to put that chore off until I was a lot drunker than I was now, but waiting wouldn’t make it any more agreeable. The contemplation of having killed people was a damn shot less pleasant than the anticipation of killing them.

Sunflower was scrubbing the worn planks by the doorway, using a gray rag that had probably been white when her grandmother opened this establishment. She glanced death and damnation at me and went on eradicating the blood trail that led up to my table.

I realized I was wet with Pup’s blood and was just starting to get sticky. I had craved a drink so profoundly I’d forgotten to change out of my murdering-people clothes and into my waiting-around-to-murder-people clothes. The realization made me feel all sunk in, like an old carcass.

My cot lay on the other side of the village, at the mason’s house. I would have paid someone a year’s journeyman wages in gold to hop over there and fetch me something clean to wear. Sadly, nobody in this town but children would fetch for me, unless it was a knife to cut my throat with, and children weren’t allowed in the tavern.

I tried to guess what Pup had wanted to tell me while he lay dying. It looked to have started with a B or a P, but I had no idea what a boy like that might think about. I propped my elbows on the table and lay my forehead in my palms, and I spent a couple of hours wondering when killing people had become so complicated.